Several Arizona State University experts are on a team that created a new way to put a price on the rainforest in order to save it, and on Friday they won the top award in the prestigious $10 million XPRIZE Rainforest competition for their work.

Team Limelight Rainforest, previously called Team Waponi, which includes four ASU professors plus more than three dozen other scientists from around the world, invented a technology to measure biodiversity in the rainforest.

They spent five years developing and refining their solution, which involves using a drone to drop devices onto the tree canopy to measure sound, record images, and take insect and plant samples.

The project combines artificial intelligence data analysis with Indigenous knowledge from the people in the region.

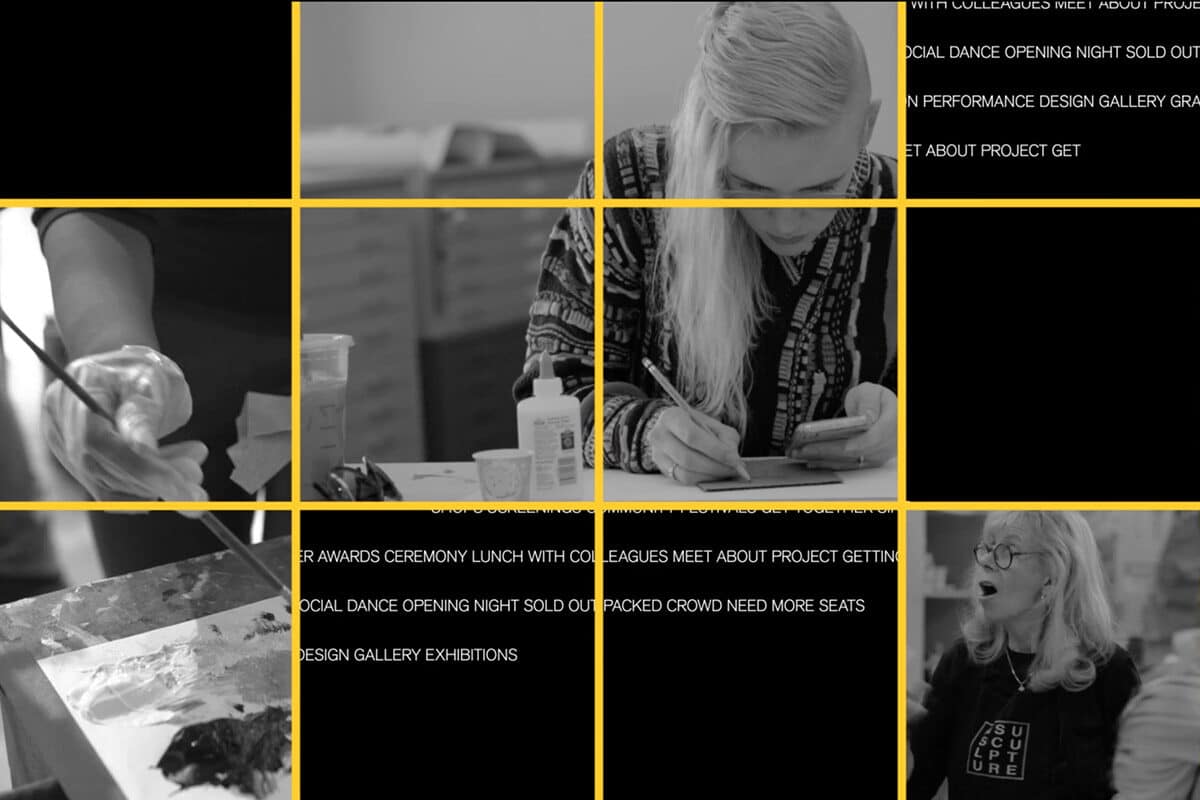

Garth Paine, an expert in acoustic ecology, created the bioacoustics recorders in the Limelight devices to analyze species density. He was thrilled with the XPRIZE victory, which was announced Nov. 5 at the G20 Social Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

“It’s unbelievable, to be honest,” said Paine, who is a professor of digital sound and interactive media in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering and the School of Music, Dance and Theatre, as well as a senior Global Futures scientist.

“This is going to affect how the United Nations values and makes international agreements about the protection of the rainforest, and that’s enormous. This is massively impactful.”

Team Limelight Rainforest was one of six finalist teams in the competition, taking home the grand prize of $5 million that will go toward further developing their solution.

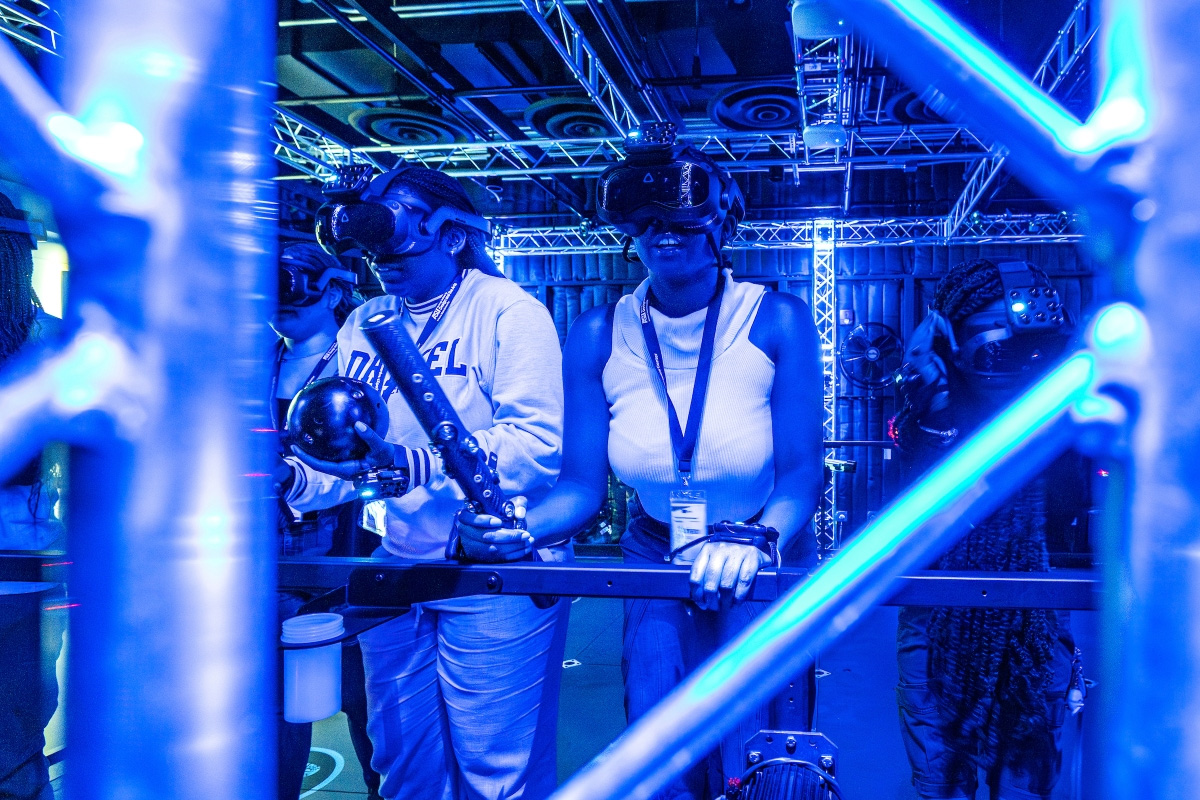

The final round was held in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil in July, where each team deployed its solution for 24 hours and then had 48 hours to analyze the results. Team Limelight Rainforest identified over 250 different species and 700 unique plant and animal populations from the 24-hour deployment, the highest amount of biodiversity observed among finalist teams.

Their solution was judged to be the most scalable and easy to use for local communities and conservationists in the field.