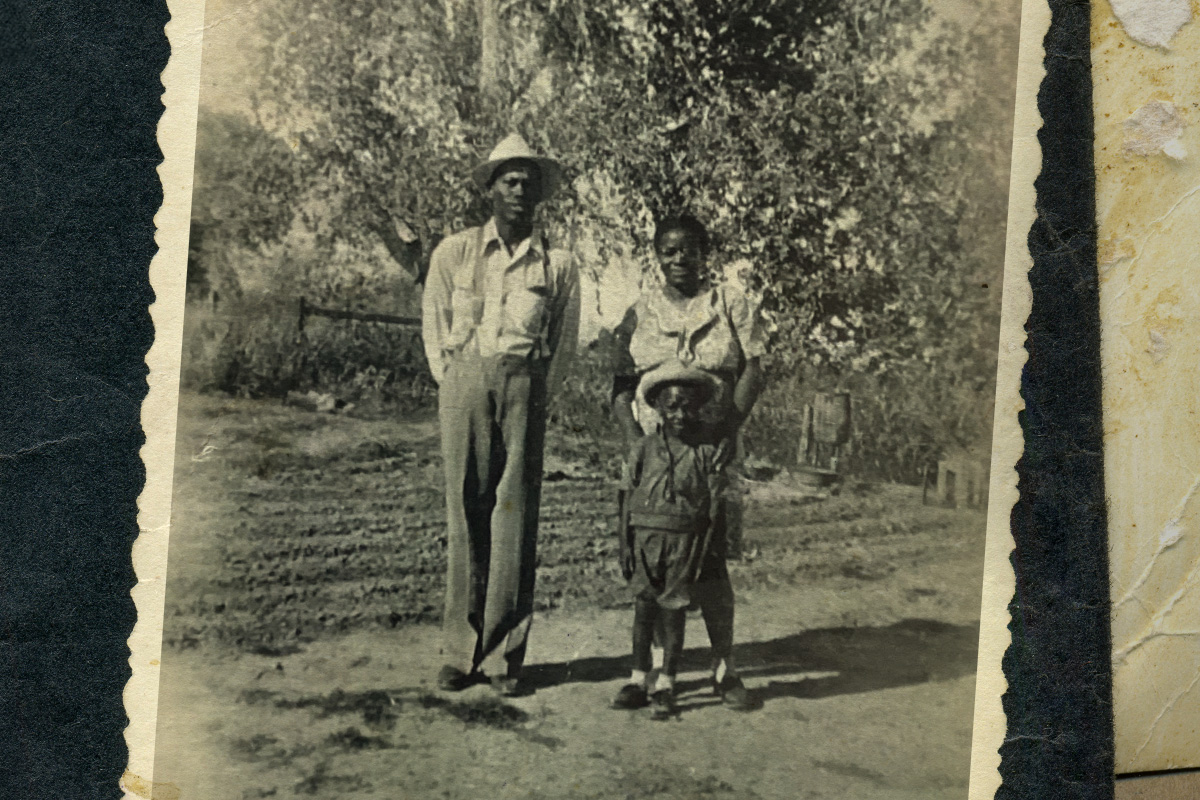

While sorting through photos in the J. Eugene Grigsby Jr. Papers, one of many collections in the backlogs at ASU Library, Associate Archivist Elizabeth Dunham often joked that Grigsby was “a total dad.”

A teacher and an artist, he traveled often to national conferences and took pictures of everything that caught his eye along the way, from random buildings “right down to the pictures out the plane window,” Dunham said with a laugh.

Grigsby’s penchant for documentation may have been considered a charming character quirk during his lifetime, but today, it’s the reason ASU Library is able to offer a unique glimpse into the life of one of Arizona State University’s first Black professors in the fine arts department.

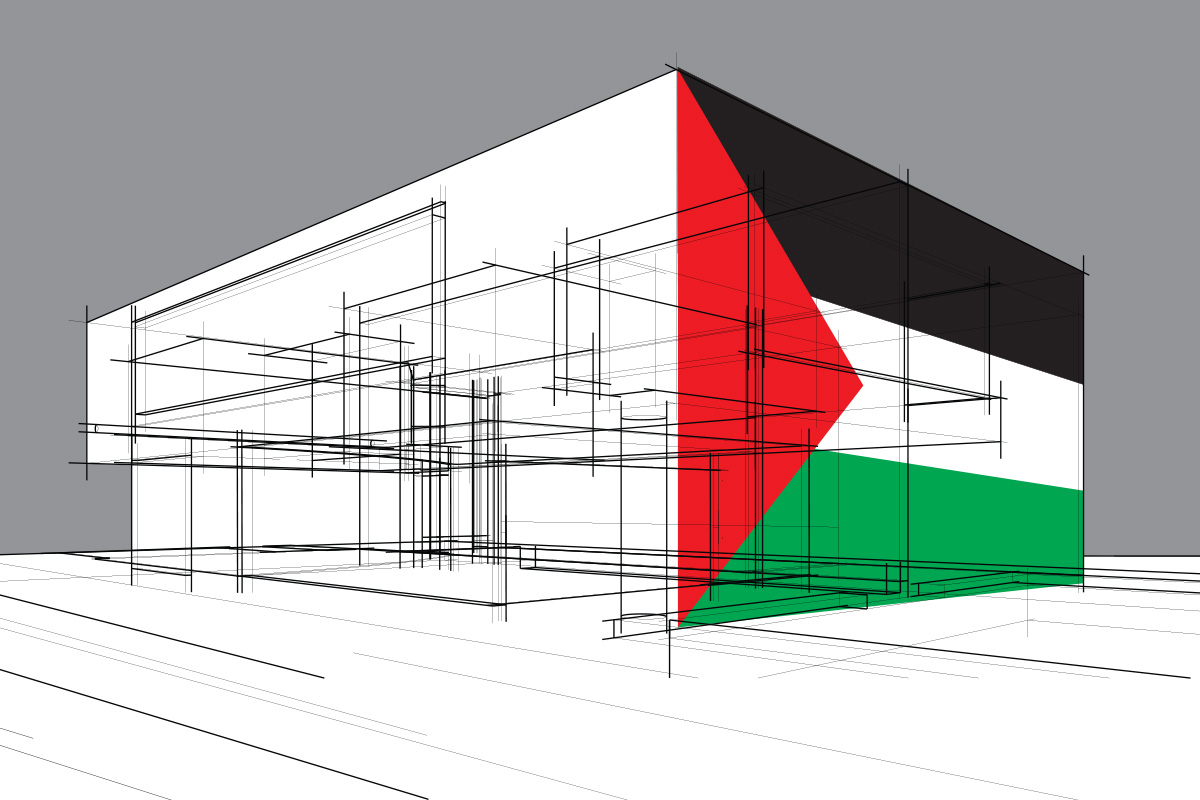

And it’s a long time coming for members of Arizona’s Black community, said Jessica Salow, who was recently named archivist of Black Collections at ASU Library, a new role for a new collection, both created as part of the university’s LIFT (Listen, Invest, Facilitate, Teach) Initiative.