Workplace wellness is not only directly related to accessibility but also engagement. Since participation and engagement are a large part of successful workplace wellness programs, another major point for the project is to incorporate technologies that will allow for more in-depth interactions and wellness readings. The plan is to leverage “off-the-shelf” and inexpensive technologies with new artificial intelligence and sensor technologies to improve the dynamics of workplace wellness.

“We need to be considerate of many issues, including cost, privacy, accuracy and latency in interventions,” Turaga said. “This means the types of instrumentation we use may be off-the-shelf, inexpensive low-grade devices, like simple pressure sensors embedded into a chair and cellphone-based assessment of posture. Our approach will leverage state-of-the-art machine learning methods that will be trained to convert low-grade, noisy and maybe even incomplete data from inexpensive sensors into information that can shed light on movement and health-related metrics. We also want to study how the job of the workplace wellness coach itself changes when they have access to such new sensors and AI-based tools.”

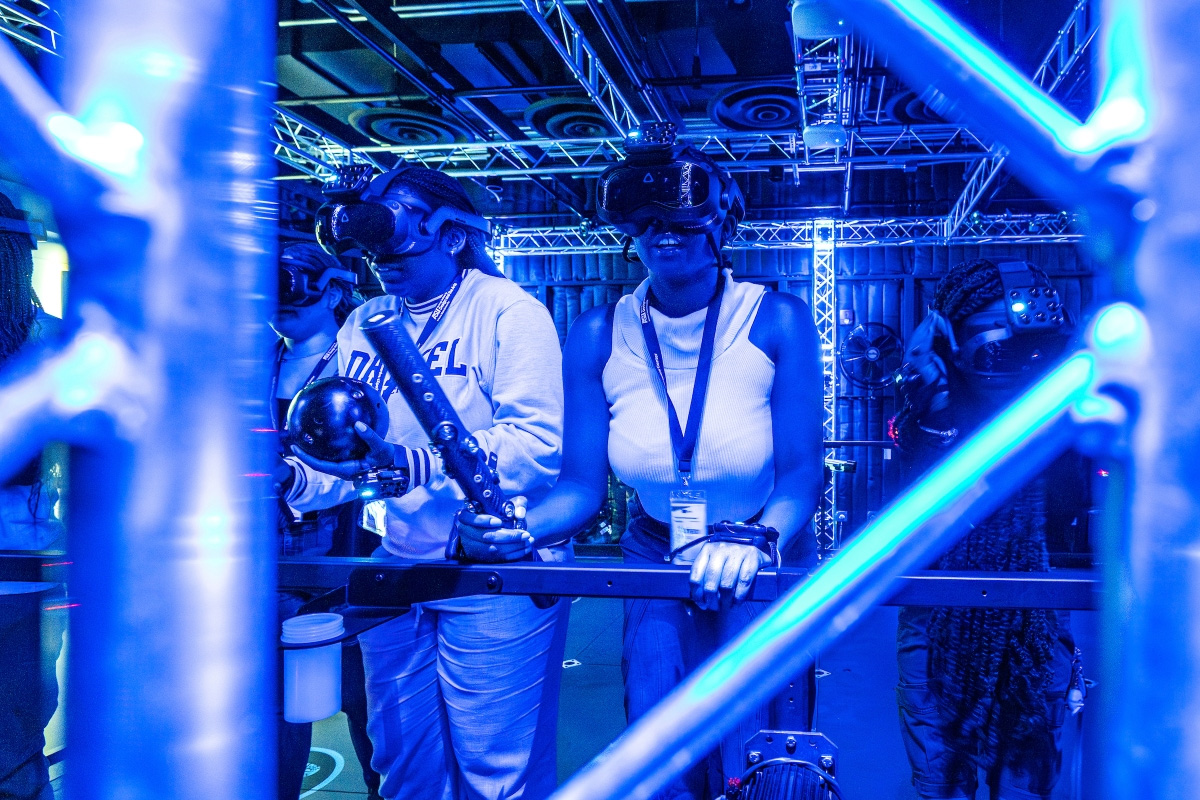

Biofeedback is key in creating engaging and accurate data, art-based biofeedback in particular. By utilizing art-based biofeedback through these inexpensive sensors and incorporating artificial intelligence, these once low-grade sensors can be more than basic means of reading activity.

“Biofeedback in our context refers to techniques that can be used to amplify and augment the sense of balance, posture and related features, so that a participant is made more aware of their habitual tendencies and inefficiencies,” Turaga said. “We seek to use a combination of auditory, haptic and visual biofeedback in our work.

“One of our focus topics will be to look at the simple activities that can be embedded into daily routines, like from sitting to standing, and making a participant aware of how the movement is. We do this action without any attention drawn to the process of movement, since it is second nature to many of us. We rarely pay attention to issues like the symmetry of the left and right sides of the body, for instance. There isn’t even an easy way to draw attention to symmetry short of standing in front of a mirror.”

“Imagine being able to computationally extract a symmetry signal from a device such as the [Xbox] Kinect, and converting it to sound,” Turaga explained. “So as you stand up, you can hear the qualities of symmetry. It is not useful, nor engaging, to have simple sounds that are repetitive and monotonous. We work with real-time sound artists who can map features of movement to higher level musical structures like phrase lengths, harmonic rhythm and tempo changes. We feel such ‘artful’ biofeedback is critical in a site like an office space, both for reasons of aesthetics, and for long-term joyful engagement.”

The idea of creating “artful” biofeedback will allow participants to become more engaged with their surroundings and aware of their physical movements. By using continuous sensing in wearable technologies, significant improvements can be made to personalize wellness protocols based on the individual’s needs. The involvement of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods will also help create better recommendations and exercises for each participant and make wellness programs more efficient.

In addition to building healthier workplaces, the team is looking into ways that wellness can reach between corporate walls. As COVID-19 continues to limit people’s ability to work from the office, people have been transforming their homes into offices. Turaga said that the pandemic has brought to light more questions about how to positively impact health and mental well-being.

“With COVID-19, homes have become offices, but many of the concerns we were looking to address still hold. Time spent sedentary is still a significant concern, probably more so now with all meetings occurring via Zoom technology. General access to external facilities to engage in health-related practices is even riskier now,” Turaga said. “Thus, investigating new solutions for the future of workplace wellness is even more important than what we had prepared for. Considerations of mental health have been brought to fore, which we wish to include as part of our planning process as we go forward.”

Creating innovative, interactive and engaging wellness programs that are available and impactful is what drives this team to leverage art, design, AI and sensor technology to better the workplace, whether through physical or mental health.