Most people’s first encounter with artificial intelligence happened on social media, when AI-generated self-portraits started popping up on multiple platforms.

It seemed like it was just fun, but then artists started weighing in—artists whose work had been “scraped” by AI and added to its toolbox, so that now anybody could make work in a particular artist’s style without actually going through the artist.

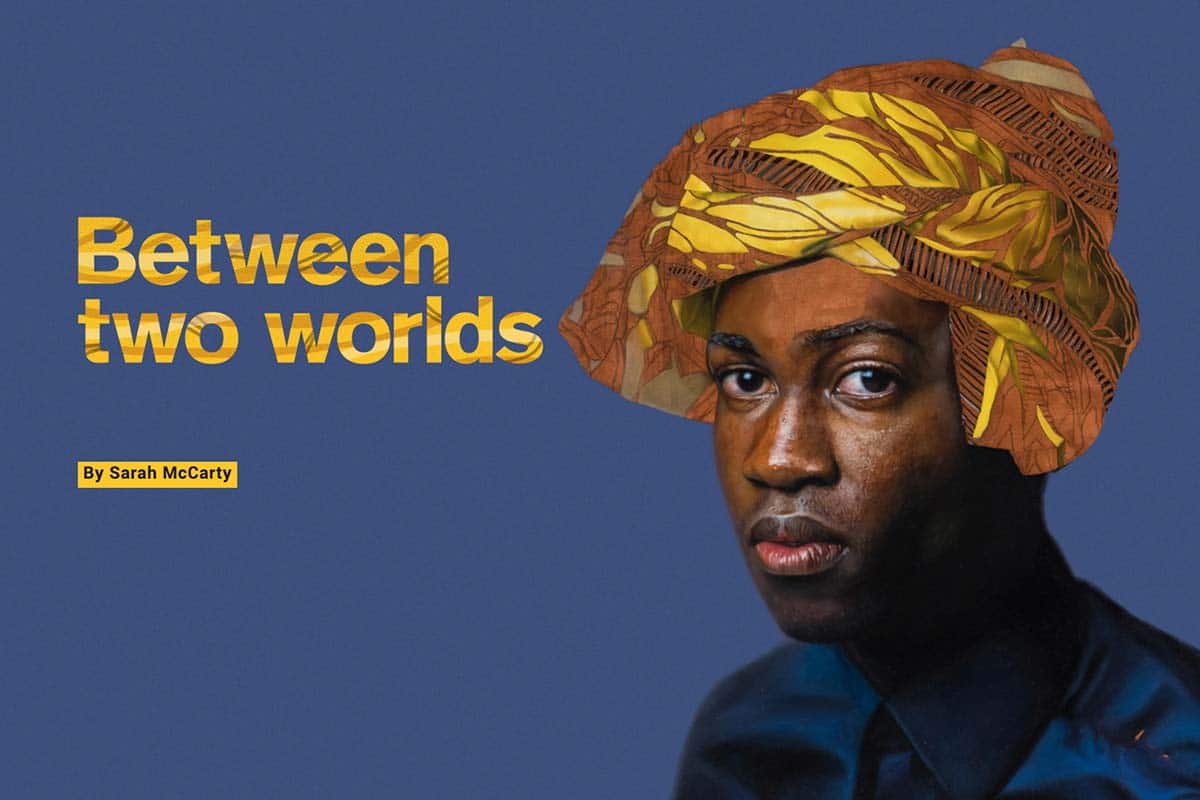

Thousands of arts and organizations have signed a statement in opposition to AI companies training their tools with copyrighted and unlicensed works. Artists, authors, musicians, actors and other creators signed the statement, including Amoako Boafo, Margaret Drabble, Kate Bush, Thom York, Kate McKinnon and Rosario Dawson.

In 2023, a group of visual artists filed one of the first major lawsuits against a generative AI company when they brought a case against Stability AI, maker of the text-to-image model Stable Diffusion, saying AI image-generators infringe on artists’ rights by using their work to learn and then producing derivative works. Corporate copyright owners have also filed lawsuits against AI companies, including Getty Images and Universal Music Group.

Shawn Lawson, animation program director and professor in the School of Art, told the State Press that while he sees potential for AI to be harnessed in beneficial ways, there are also concerns with the information that AI tools pull from when learning.

“That text information is biased, based on the person who is putting in that information in terms of what their tagging that data is,” he said.

Herberger Institute Professor Wanda Dalla Costa also shares concerns over obstacles to inclusiveness when the data used for training AI is from a limited population.

“Whose sentiments are you aligning to?” Dalla Costa asked during a panel at the ASU’s Smart Region Summit in March.

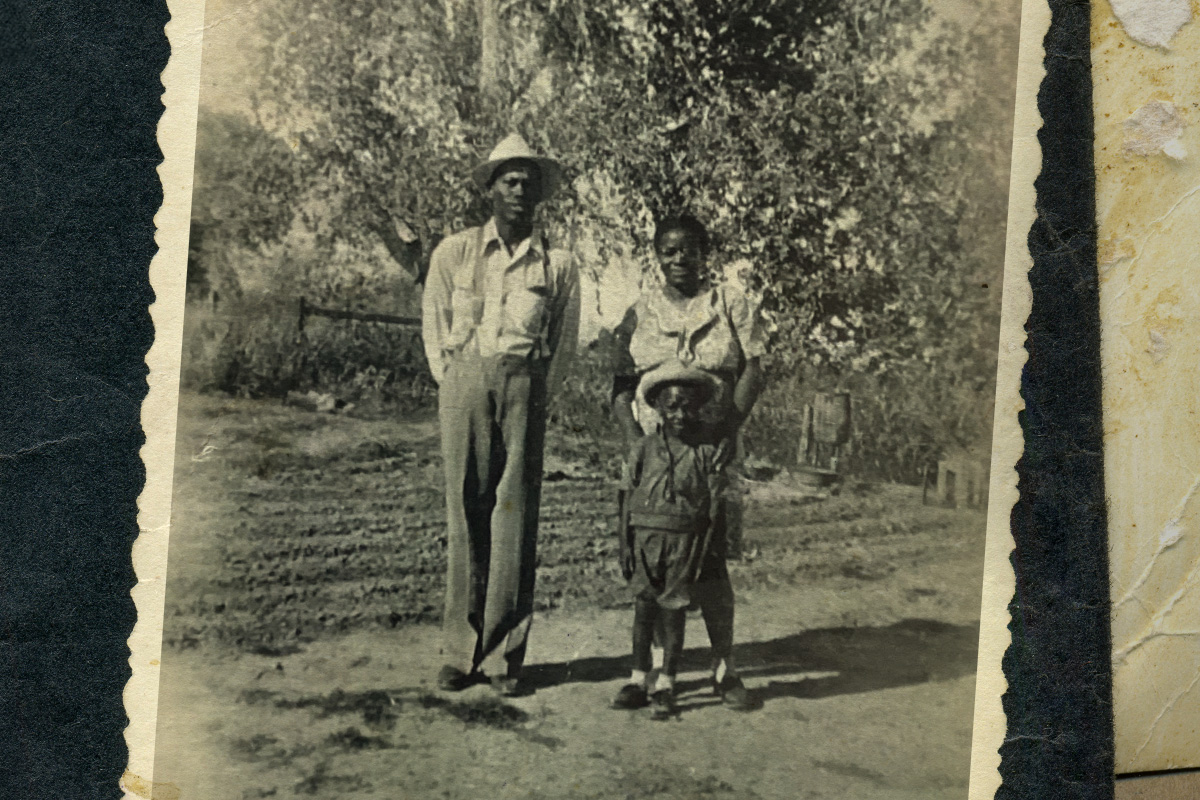

She said that although engineers may make use of alignment — a process of encoding human values into large language models — there is invisible data, such as oral traditions, that is not counted.

“This perpetuates … layers of systems that work against many communities of color and voices that have not been recorded,” Dalla Costa said.

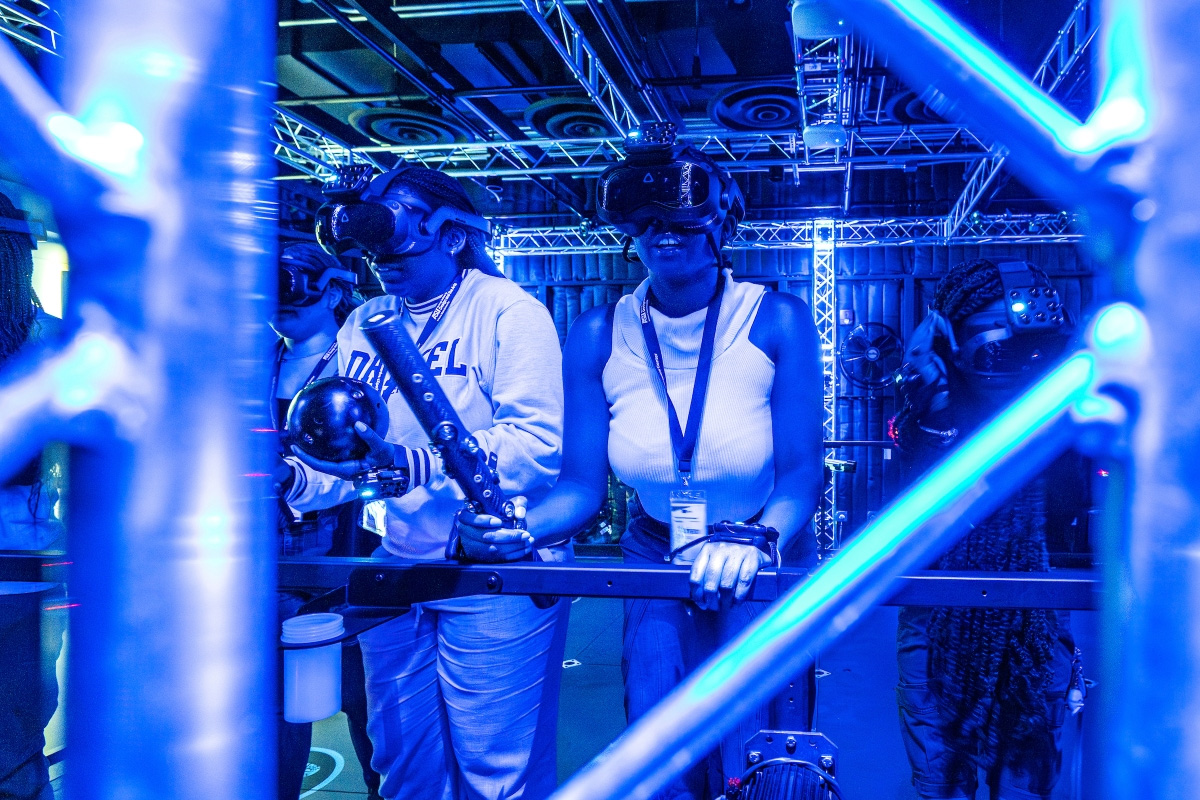

Understanding both the limitations and the possibilities of AI is something Lance Gharavi hopes ASU can teach students. As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at the university, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.

Gharavi, a professor in the School of Music, Dance and Theatre in the Herberger Institute, has been teaching a new course this semester called “AI Literacy in Design and the Arts,” which covers the benefits, challenges and ethics surrounding AI.

Gharavi has been working with the provost’s office since 2022 on how to teach AI literacy, and then collaborated with curriculum designers and content creators to build the course as the semester proceeds.

The course, which will be offered again in the spring, is designed to serve as a template for AI literacy courses in other disciplines.