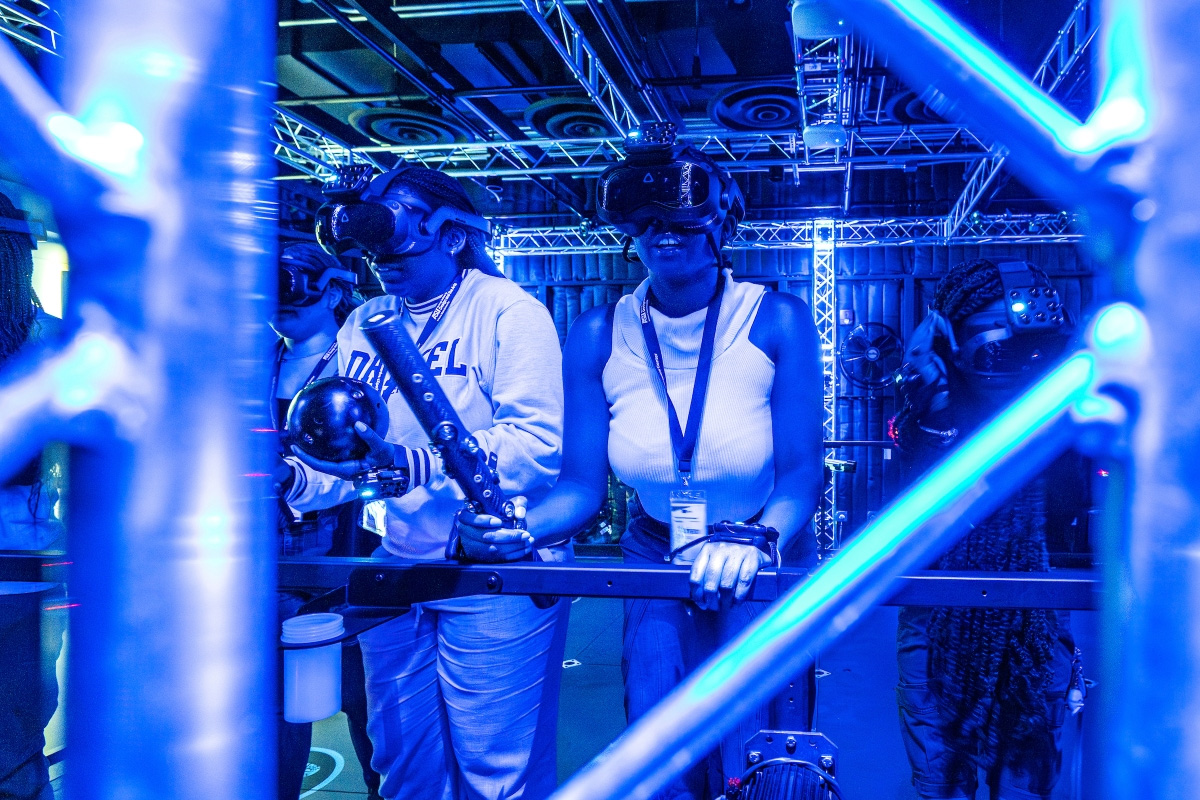

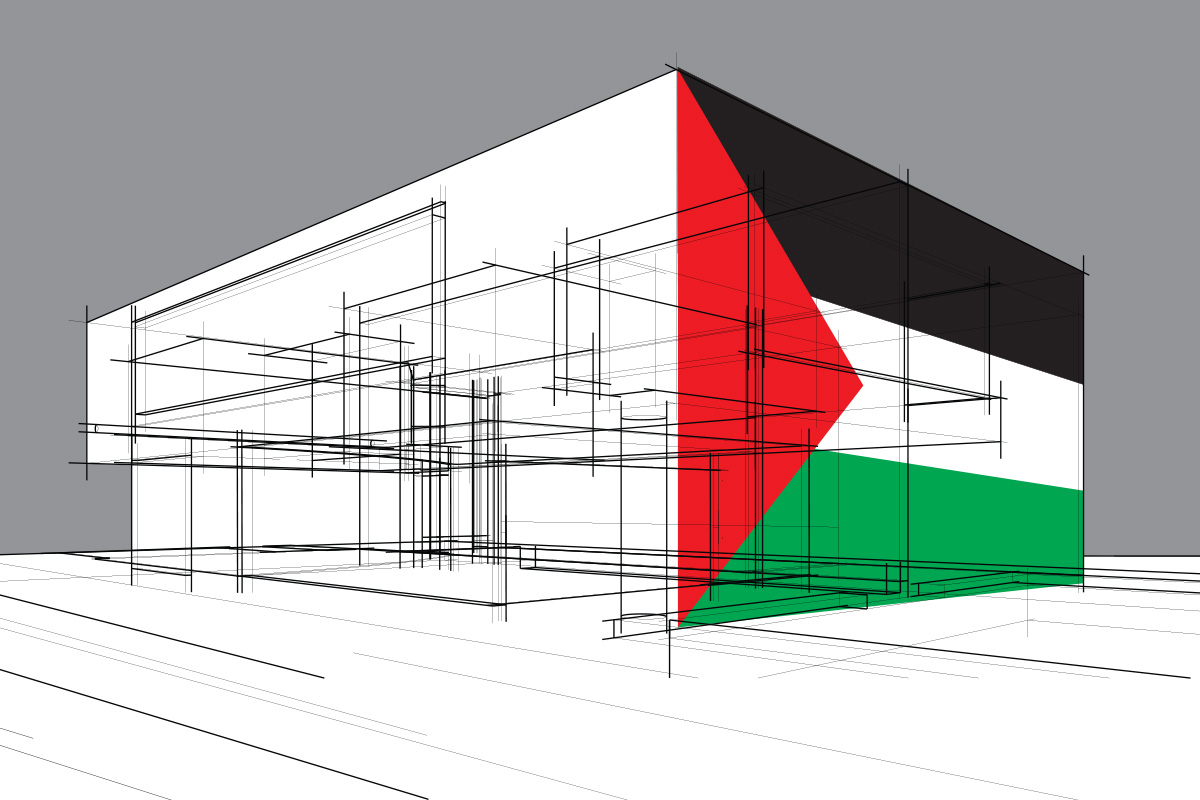

A class of Arizona State University architecture students collaborated with peers from a Palestinian university this year on a project to reimagine a kindergarten building for children who are living amid conflict.

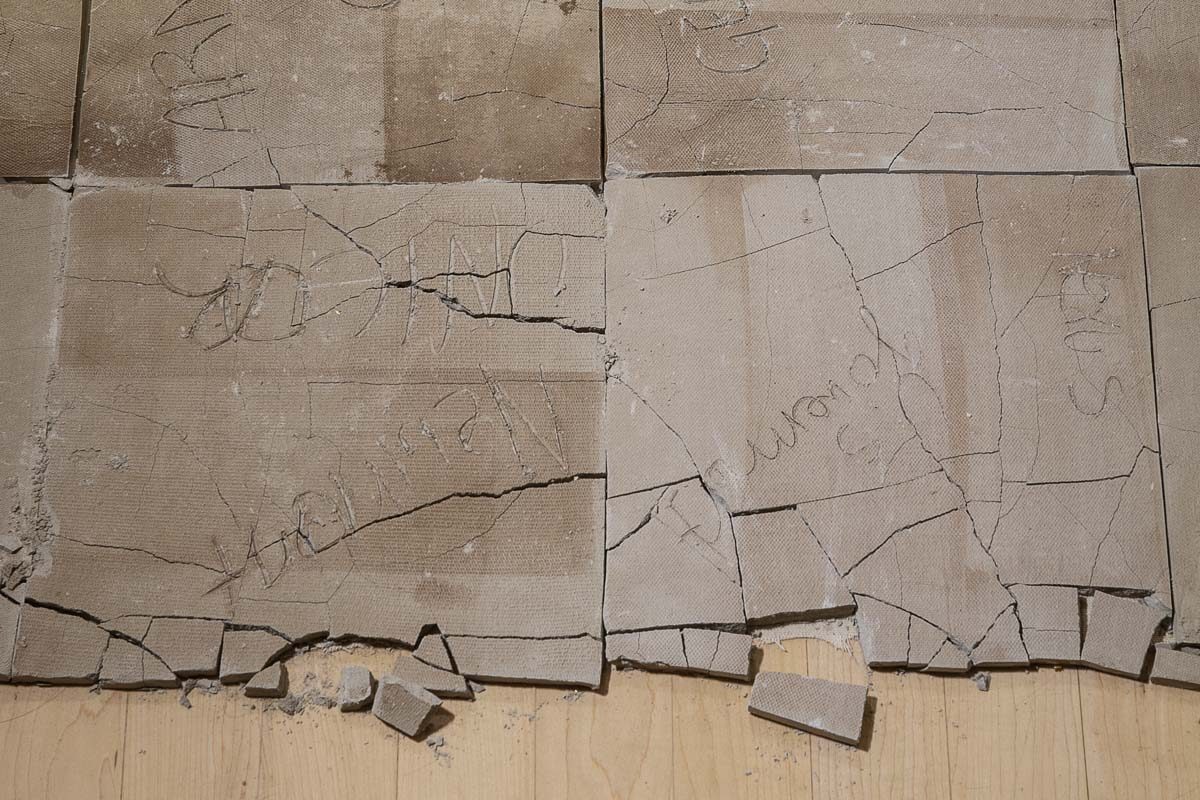

The Sun Devils came up with creative designs like a treehouse, “reading tents” and an alphabet wall as they learned about Palestinian culture from students at An-Najah National University. The two groups worked on a renovation for an existing kindergarten building in Nablus.

“The cultural exchanges were very touching and not only was it fun to learn from people across the world that otherwise I wouldn’t have contact with, I also enjoyed seeing how they worked,” said Uor Fawzi, an ASU student in the course.

The Climate Futures Exchange is a project of the Center of Building Innovation, an interdisciplinary center in The Design School at ASU. It’s funded for two years by a $300,000 grant from the J. Christopher Stevens Virtual Exchange Initiative, a U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs program administered by the Aspen Institute.

The exchange included a lecture course in the fall and the studio in the spring, both of which will be repeated next year. The funding paid for a graduate assistant, technology and related events, according to Phil Horton, a clinical associate professor of architecture and co-director of the Center of Building Innovation.

Horton had worked with faculty from An-Najah University on a studio project in 2017. In that year, the two groups of students collaborated on infrastructures such as community gardens and solar-shaded plazas for the Balata refugee camp in the West Bank.

Originally, this year’s project also was going to address the refugee camp. But on Oct. 7, the Hamas terrorist group attacked Israel, which led to ongoing counterattacks by Israel on sites in Gaza. Horton said the faculty decided to pursue a project that was more uplifting and found the kindergarten renovation plan via an alumna.